I’ve been musing on a few things.

A few weeks back, I attended a workshop about resilience in the writing life. It was packed, and most of the attendees were women. I got chatting to some of the other writers about the fact that difficulties – emotional challenges due to the highs and lows – in the writing life are part and parcel of the whole thing. We all know it’s true. But somehow, we agreed, these are things we don’t seem to talk about openly enough .

Then, the other day, someone I know shared a great list on twitter of self-care tips for writers that really hit home (I shared them on my timeline). It started me thinking about the deep-seated issues and beliefs that were driving this and realized just how many self-defeating myths we subject ourselves to.

Often, I think, it’s because writing is so personal. In fact, the better we are doing it, and the more honest we are, the closer to ourselves it will seem. But at the same time, the writing world is not an easy one. Writing, particularly when you are starting to get published and get your work out there, can be incredibly competitive. It can be harsh and unforgiving, and we can be overly hard on ourselves.

Here are some of the pernicious myths that can get under our skin as writers and do damage if we don’t take steps to question them, and give ourselves a little bit of self-care.

Myth 1: Our Writing is Us and We Are Our Writing

Because writing is so personal, and often what we write about is in some ways a reflection of ourselves, it can be very hard to separate ourselves as people from the work. Now, when we are actually writing, and digging deep for our truths, this is often an advantage. When we send our writing out into the world, however, it is a different tale.

It’s important to try to detach ourselves from the work.

A story is not “us” – it is merely from us and is ultimately, just a piece of writing. It is part of our artistic development, whatever happens. The truth is, it may do well out there in the world; equally, it may not. Yes, we can do what we can to prepare it as best we can, but it is no reflection on our worth as people if it does eitherwell or badly. Set too much store by it, invest too much of your ego in a piece of work and you can end up either a raving egomaniac, or a quavering fruit-loop. I’ve certainly done both. Easier said than done, I know, but best to aim for neither.

Send work out, and once that’s done, try to forget it – and work on something else as soon as you can.

Myth 2: Our Value as a Person = Our External Success as a Writer

“Who are you? Are you an important writer? Are you someone I should’ve heard of?”

You may know this drill, or have seen it happen to others

And then there’s “Ahh, you’re THAT person who did that great thing! I’ve heard of you!”

No pressure, then!

It follows from what I was saying above, really. Of course recognition of our achievement is great. We should be proud when it happens and own it. But don’t let it take over. Don’t become a legend in your own lifetime. (That said, isn’t it a satisfying feeling to reveal oneself after a very obvious underestimation? I’ve seen it happen to women writers a lot, especially the older ones.)

I really do think it’s important not to come to rely too hard on getting that external approval. You need to be able to carry on without it. And trust me, a bad review can crumple anyone to the floor, including bestselling authors. Times change; writers have their peaks and troughs. We have to find a way of keeping on whatever happens and remind ourselves we’re playing the long game.

Likewise, what if we worked really hard on something that didn’t get anywhere – have we failed as a person? No. We live to write another day. We tweak it, perhaps, and see if we can send it somewhere else. We rest it for a bit and come back to it with fresh eyes. And you know that old thing about your last minute emergency back up being “the one that brings it home?” – well. Think on. So no, your value as a person does not rest on your external success as a writer.

We are not in charge of the outside world. We can’t control others’ opinions or preferences. We are not what other people think. We are not in control of Acts of God or the bizarre quirks of fate that get in everybody’s way sometimes. All we can do is keep the focus on what we’re doing. The work itself is the bit that’s up to us.

Myth 3: Our Writing’s External Value Is Its Only True Value

A writing tutor I know of apparently told their students that if their writing wasn’t published, then the writing didn’t mean anything. As if it was only “real’” when others – him, presumably, or someone he deemed sufficiently important – saw and approved its existence.

I hate stuff like this. Such bullshit.

I understand and agree that the world won’t know us if we don’t share our work, and so we should, when we decide we are ready. But you can’t rely on other people to tell you your work is Important. And should you stop writing completely if you and your work are never going to be deemed Important by some arbitrary measure or decree? Should you give it all up if you never win the Booker, or don’t become a millionaire?

Of course not.

It’s that external validation thing again.

I’ve always cringed when I hear that word “important” being referred to either work, or artists, of any stripe. It smacks of pomposity to me. “Interesting” yes. “Groundbreaking” yes. And it’s good to have ambition – the ones we set for ourselves, although as I said above, we should avoid having ambitions where we have no control over the outcome.

Written work in all its stages has value. We may not even send it out into the world, but creating it, shaping it, making it something we want it to be, can still be profoundly satisfying. I’d think less about “out there”. I’d think more about “here, this, now.”

Myth 4: Productivity is Everything

Look, some people are designed to churn out thousands of words at a rate of knots. And some people aren’t. Don’t beat yourself up. I know loads of slow but excellent and careful writers. I know highly talented writers who send out two stories a year. And then there are writers who whip out book after book after book super-quickly and I’m amazed at their efficiency. Not to mention jealous.

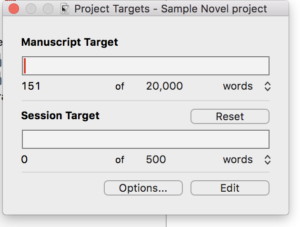

Also – it’s not all about wordcount. I appreciate that sometimes we get held up by procrastination, but there is nothing wrong with projects that you just noodle along with for the love of them and that you just do for you. You don’t have to do the Protestant-work-ethic whip-whip-whip thing.

We are allowed to play sometimes. We are allowed to take a break. We are allowed to do things just for fun. Everything doesn’t have to be professional, everything doesn’t have to be published. And remember we’re allowed to give ourselves a rest.

Myth 5: Perfection is Everything

As above. Everything can’t be perfect all the time. It doesn’t have to be. A need for perfection is one of the biggest causes of writer’s block. What we do doesn’t have to be perfect. The first draft of anything is shit, as Hemingway said. Don’t get it right, get it written. Have fun. Lose yourself in the project itself, not where it might be going and who might eventually be looking at it.

We don’t have to be perfect. We don’t even have to be good.

Myth 6: Write Every Day

OK, so in fairness, I do prefer to do this. And I often feel tetchy if I don’t, although my “writing” doesn’t have to be wordcount-increasing necessarily. I just like to put pen to paper – or fingers to keyboard – on a daily basis, or I feel like it’s all building up and I find myself annoyed.

But it’s one of those ‘”rules” that gets decreed everywhere and honestly – we don’t have to. Some people write every day. Some people a bit here and there on the train, or at the weekend or on their days off from work. Yes, time can be a factor. You’re not a useless failure if sometimes life gets in the way.

Nor if we get stuck. There are various ways to get around this, but you are not a quitter if you give it a rest for a few days. Sometimes – and you will know what your own patterns are – it helps to consciously do no writing at all for a day or so. Stick your story or novel or project under the bed, go and have a few days of life and see people and do things. Forget the pressure you put yourself under. Leave it for a bit. Return to it when you are fresh with your batteries and creativity recharged.

I hate Decrees-From-On-High about how we should think and feel, and it’s pernicious myths like these that we internalise and allow to stop us in our tracks. But we can make our own writing lives by noticing when these kinds of myths come up for us, challenging them, and creating a writing life that works for us.

The author of this relatively recent and increasingly popular book is TV producer John Yorke, ex-Head of Drama at Channel 4 as well as former Controller of Drama at the BBC. So it’s fair to assume that Yorke is a guy who knows his stuff with regard to story and narrative structure.

Screenwriters and fiction authors. One group writing to meet the often harsh demands of the film and TV industries, the other striving to create Booker-winning literary masterpieces. Different markets and forms, different audience. In other words – with about as much in common as cats and dogs. Or so you might think. What could one group of writers possibly have to teach the other?

Screenwriters and fiction authors. One group writing to meet the often harsh demands of the film and TV industries, the other striving to create Booker-winning literary masterpieces. Different markets and forms, different audience. In other words – with about as much in common as cats and dogs. Or so you might think. What could one group of writers possibly have to teach the other? 1. It’s All About The STORY

1. It’s All About The STORY